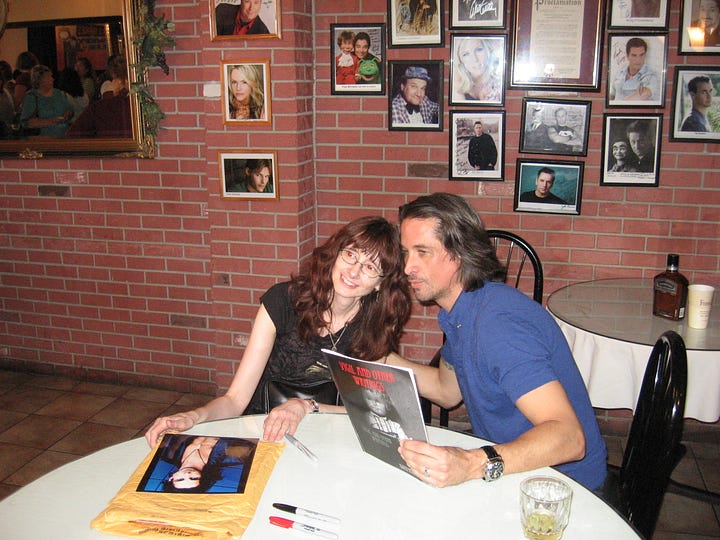

Michael Easton and Caleb Morley

Actor/author/filmmaker Michael Easton and his portrayal of the vampire Caleb Morley

These photos of actor/author/filmmaker Michael Easton brings back memories of the many events I have attended in California, New Jersey, NYC, Philadelphia, and Chicago and elsewhere to see him. I first became aware of Michael when he was portraying the vampire Caleb Morley on the cancelled ABC daytime drama Port Charles. Although I have been fascinated with vampires since junior high and have seen many films about them , Caleb, as portrayed by Michael Easton, was, in my opinion, the most intense, alluring, multifaceted of them all. When I found out that Michael was also a poet, screenwriter, and graphic novelist, as well as an actor on various TV shows and films, my interest in him deepened. (Some of my reviews on Michael’s writings, are listed here on my Horror Vacui site:

https://horrorvacui.us/my-review-of-18-straight-whiskeys/

https://horrorvacui.us/review-of-michael-eastons-credence/

The following essay, written a few years ago, I had planned to include in a book analyzing the Caleb character as he relates to the depiction of other vampire figures and horror archetypes in film and literature. I had written several chapters in the book but decided, for now, to release them instead as separate essays.

Horror Antihero Caleb Morley:

Analysis of the Vampire Caleb Morley

Although daytime dramas, better known as “soaps,” began as languorously-paced, narratively-anemic television stories designed to divert the house-bound wives and mothers while promoting sanitizing domestic products, they evolved into increasingly convoluted melodramas depicting adultery, murder, mental illness, and whatever social problems or taboos enticed their progressively more diverse audience. Deranged twins, falsified medical records, long-presumed dead siblings or children miraculously wreaking havoc upon their scheming relatives are now standard plot devices in the once-prosaic realm of homes, hospitals and detergents. Despite the often implausible storylines, however, the daytime drama genre has rarely ventured or sustained forays into the supernatural. Whereas a few soaps have briefly featured plot elements involving ghosts or demonic possession, “Dark Shadows” was, for years, the only soap that continually delved into otherworldly scenarios. In 2001, however, the General Hospital spin-off Port Charles, originally, like other soaps, focused on romance, intrigue, deception, and betrayal, followed Dark Shadow’s example by introducing supernatural storylines about magic and vampires. The most compelling and creatively inspiring of these storylines focused on the vampire character Caleb Morley, portrayed by actor Michael Easton. Not only were these stories intriguing and innovative in their portrayal of vampires, but they also included immensely perceptive explorations of psychological and spiritual conflicts that have afflicted people for centuries. Like the works of Edgar Allan Poe , Joyce Carol Oates, and Robert Louis Stevenson, among other writers of horror-themed literature, Port Charles used imagery of the vampire, the sinisterly seductive stranger, and the doppelganger as a way to explore mysteries and aberrations of consciousness, the monsters within.

A key theme of Port Charles and horror in general is duality, the battle between good and evil. As in many horror films and literature. Port Charles dramatizes this dichotomy by having one character, the vampire Caleb Morley, associated with evil, and some of the other characters, particularly the angel/vampire slayer Rafe Kovich, represent aspects of virtue. This apparent dichotomy, however, reveals layers of ambiguity, mirror doubles reflecting latent desires and fears.

Dream demon, seducer, taker of souls and infester of visions, the vampire Caleb is the stranger we know from somewhere deep within ourselves. He offers those willing to surrender to him a thrilling journey from which we may never return, a dangerous expedition into our primal selves. The wildness and darkness Caleb releases in those he has touched is as ancient and potent as the first bloodstained, firelit gods scrawled on cave walls. He lurks within human consciousness, taking many forms, many guises as he is summoned from his slumber by the dreams and invocations of questing, restless souls

A shadowy figure with fierce, entrancing eyes, Caleb is a tantalizing voice trickling into an innocent girl’s ears, a demon shaman hitchhiking his way into her yielding soul, a seductive stranger who offers dazzling gifts that come at an undisclosed price. Will he ravish the body or gnaw away at sanity? Does he lead into damning temptation or release one into the limitless depths of imagination? Only by giving oneself up to the perilous but potentially illuminating possibilities he promises can the answer be revealed.

Like the Wolf in the “Little Red Riding Hood” fairy tale, he can assume a charming guise, luring his prey with sweet, gentle words, as he does with his soul-mate Olivie (Livvie) Locke, or, for those who unknowingly thirst for excitement, such as the young, romantic Gabriela Garza, he can tempt with forbidden pleasures. At times he offers both danger and magical romance, promising an eternal unconditional love that is attainable only by sacrificing one’s human existence and all mortal ties. During their first conversation (by the river, a symbol of transformation), for example, Caleb tells Livvie that he is her “future,” the one who can take away her grief and loneliness; all she has to do, he murmurs, is “surrender,” and her emptiness will disappear forever. He invades her dreams, becoming the secret lover, the erotic phantom who knows what she desires and is the only one who can satisfy her, the only one who can love the darkness and torment harbored within her lost little girl soul.

Caleb’s seductive enticement and ability to peer inside one’s psyche has similarities to the mysterious temptations offered by A. Friend in Joyce Carol Oates’ short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been,” a mysterious character who appears to a teenage girl (Connie) and proceeds, by sweet talk and threats, to seduce her into going for a ride with him in his flashy gold car. One of the most intriguing aspects of Oates’ tale is that, as with Caleb, A. Friend seems to exist as a fantasy lover, evoked by the unconscious libido, a demon who knows one’s deepest needs and darkest secrets.

Like the girl in Oates’ story, Livvie at the beginning of “Tainted Love” is a young woman with two sides to her, an innocent “good girl” side and a more rebellious, thrill-seeking, defiant side. After Livvie meets Caleb, she, like Connie, is forced to choose between two worlds. Livvie must decide whether to continue living in an illusory, childlike world, represented by her boyfriend Jack, or let herself experience the dangerous passions and forbidden knowledge represented by Caleb. By choosing Caleb, Livvie forsakes human notions of love and security for the fierce, transfiguring, soul-scarring love binding immortals throughout eternity.

Relishing his status as an immortal bloodsucker, Caleb embraces the arrogant, ruthless powers of the defiant damned. Cruel, mocking, treacherously alluring, and nearly invincible, Caleb savors his wicked ways and considers himself to be far superior to the beings he depends upon for sustenance. Stalking, deceiving, and murdering, Caleb terrorizes Port Charles and brainwashes his beloved Livvie, stealing her innocence and forever tarnishing her soul. Even after Caleb is killed twice, struck by lightning, then stabbed in the heart by Livvie, he remains as indestructible and inescapable as a dream, returning to haunt his beloved, as well as the rest of Port Charles, by assuming the guise of the enigmatic, mesmerizing rock star “Stephen Clay.” The first glimpse of him in his new identity is in the shadows of a limousine. Like A. Friend, he uses sinister charm to entice his young female prey. Smiling cryptically and somewhat lewdly at young female songwriter Marissa while sitting beside her in his limousine, he claims to see inside her soul, know her better than she knows herself. “Take a little ride with me,” he urges, luring her away from safety and drawing her more closely into the enclosed, womblike darkness of his limo. Later, after Marissa is dropped off at her destination, “Stephen” sees the innocent, virtuous waif Tess wandering aimlessly in the park and offers her a ride. “All you have to do is get in the car,” he tells her, warning her of the dangers she may face by herself in the park. Although Tess declines his offer and begins leading a life of bland domesticity with Livvie’s boyish cast-off, Jack, she later finds herself irresistibly pulled towards the dark, fiery intensity and passion she perceives in Stephen/Caleb. As with her lookalike, Livvie, she cannot resist her attraction to this seductive stranger.this potential threat or possible savior who seems to know her most private hopes and fears, who offers escape from boredom, loneliness, stagnation, or despair. Taking a “ride” with this stranger can bring death, transformation, or shattering self-knowledge, but few can turn away from his perilous, poisonous magic.

Caleb’s dual nature goes beyond his role as a vampire, giver of death or eternal life. Just as we think we understand his motives or begin to perceive him as merely another intriguing but unredeemable villain, he reveals yet another conflicting facet of his personality. Early on in his story, we see him depicted as the villainous counterpart of his priestly identical twin, “Father Michael.” Lurking in the basement of Father Michael’s monastery, he glares with fiery, beast-like eyes, a phantom dream-embodiment of sin in a sanctuary of virtue. He is sensed by the flakey yet psychic Lucy Coe as an ominous force, appearing to her as the Stranger card, cloaked and sinister, in her Tarot deck.

Caleb is too complex, too ambiguous, however, to be confined to the vampire’s customary realm of evil. Although Port Charles, as is typical of classic horror films, externalizes the conflict between evil and good with its depictions of the vampire and his/her virtuous nemesis, it differs from the typical Universal horror films of the ‘30s and the Hammer vampire horror films of the ‘50s through ‘70s by exploring in considerable depth the inner conflict of its characters, particularly Caleb.

Although on the surface Caleb appears to be the embodiment of pure evil, he is actually much more vulnerable and tormented than he will admit. Torn between a murderous id and a moralizing superego, Caleb’s intense inner conflict takes the form of a dual personality disorder. Like Norman Bates in “Psycho,” Caleb is split into two relentlessly battling aspects, and neither Caleb nor his priestly “twin” Father Michael realize that they are actually opposing aspects of the same consciousness. His first screen appearance on Port Charles, in a dark basement of a dilapidated church, vividly symbolizes the antithetical dualities raging with him. Throughout this scene the basement is lit in a gentle, ochre light, dusky and foggy yet pierced in areas with golden rays which illuminate Caleb’s face, making him appear like some radiant, almost holy figure in a Da Vinci or Caravaggio painting. Both Father Michael and Caleb in their scenes together (which are, of course, before it is revealed that they are the same person) have a mystical, ethereal glow. Caleb’s menacingly glowing eyes and his wild, predatory demeanor, however, contrast with the golden aura surrounding him. He is like a beast imprisoned. The basement, symbolizing the id, the savage impulses lurking in the darkness of the unconsciousness, shelters him in its protective yet confining womb, while the church, representing the superego, morality and spirituality, towers above its dank foundations. Apparently unaware that his pious “twin” is merely a creation of his divided psyche, Caleb hides in the shadows as his other aspect struggles to rebuild the derelict church. Unlike traditional vampires, Caleb is immune to the sacred symbols that traditionally repel those of his kind. Escaping from seclusion, Caleb defiantly enters the church, touches the crucifix in a mocking yet somewhat reverent manner, and attempts to destroy all the hard work “Michael” has done to restore the beautiful old chapel.

In a clever twist of the good/evil dichotomy, both aspects of Caleb, the vampire as well as the priest, appear to be incited into battle against each other by their mutual attraction to the same woman, an unmarried pregnant woman with the Biblical name “Eve.” The shy, gentle “Father Michael” gains Eve’s friendship with his kind demeanor and spiritual insight, but despite his chivalric gestures, he seems to harbor unacknowledged feelings of desire. Like the slyly slinking serpent in the Garden of Eden, Michael hands Eve an apple, symbolic of forbidden temptation. Although “Michael” tries to conceal his lustful feelings from Eve and himself, he cannot hide them from Caleb, who continually reminds Michael of his secret sin. Caleb likewise covets Eve but for a different, far more malevolent reason; he wants the fruit still ripening inside her, the as-yet unborn child he plans to steal after it is born and raise with his true love, Olivia, as their own baby. This yearning for his beloved and a family of his own is one of Caleb’s few weaknesses, one that Michael can use against him, for, as Michael rather cruelly reminds Caleb, vampires cannot reproduce. Michael, the celibate but love-smitten priest and Caleb, the lecherous but infertile predator, share the loneliness of a family-less life. Both are outsiders, observers of human experience denied to them, but whereas Michael feels love and compassion for the human world, Caleb feels hostility and resentment.

Just as Norman Bates protects his murderous “mother,” Father Michael shelters his vampiric alter-ego deep within the bowels of his church, Caleb’s dangerous impulses symbolically suppressed by the spiritual, moralizing superego. Caleb, however, continually battles his constricting, compassionate protector, usually triumphing over his priestly counterpart. In a particularly chilling scene Caleb breaks free of his repressive priestly alter-ego, and, still wearing his priest’s robe, stalks Eve. Hearing what appears to be a conversation between Father Michael and someone else, Eve enters the church and sees the priest by himself, his back to her and still talking to an invisible presence. He senses her presence, and, without turning around, urgently warns her to leave. Concerned for her friend Michael’s safety, she refuses to go away, and by the time she realizes what is happening, it is too late. Father Michael is no longer there, his body and soul now controlled by Caleb. This scene in which the priestly-garbed figure turns around and reveals himself as Caleb evokes memories of Psycho as well as The Night of the Hunter. It echoes the Psycho scene in which one of the female characters, searching the basement for clues, sees what she believes to be old Mrs. Bates sitting on a chair, only to discover, in horror, that the old woman is actually the shoddily preserved body of Norman’s mother, the eyes staring back at her as dead, glazed, and ominous as the many stuffed birds of prey Norman has arranged in frozen flight around the dank, musty house of gloom. Although Caleb, in obvious contrast to the gristly Mrs. Bates, is beautiful and breathtakingly alluring in his menace, he is as cold and sinister as a basilisk with his eyes of death. This scene, with its chilling blend of holy and demonic imagery, also shares similarities with the classic thriller The Night of the Hunter. Like the murderous reverend in Night of the Hunter, evil conceals itself behind a religious persona. Caleb, still wearing the priestly collar of Father Michael and otherwise identical to his twin, appears horrifyingly different—his fixed, serpentine stare of loathing diametrically opposed to Father Michael’s shy, kindly demeanor. An othewordly being, indifferent to human suffering, he glows with the luster of a Byzantine icon or a hellishly brilliant devil. Eve watches in horror as Caleb, disguised as her friend Michael, threatens to steal her unborn baby, even if he has to rip it from her womb. Realizing that Caleb and Father Michael are the same person, Eve cleverly decides to coax the sweet, compassionate priest from within the malevolent vampire.

She calls upon Michael, the sweet, shy, sensitive man who befriended her, sheltered at his church, and helped her find her way back to her beloved Ian. Her insistent summons somehow sneak past Caleb’s cruel bravado and bring back his gentle alter-ego. Back and forth the split personalities, demonic god and anguished priest, battle. Seized by convulsions, the Caleb/Michael hybrid staggers, grips his stomach and retches. Like werewolves and other shape-shifters, Caleb is possessed by two opposing aspects of his personality, but in Caleb’s case the transformation is much less visible, revealed only in his facial expressions, voice, and demeanor. “One soul,” the Michael aspect tries to remind his arrogant, vicious Caleb counterpart. Caleb may think he can break away from his more human, vulnerable side; however, the two aspects are one being.

In the end it is this vulnerability, Caleb’s love for Livvie, his addiction to her, that proves his undoing. Killed by a lightning bolt in “Tainted Love” and by Livvie’s stake in “Tempted,” Caleb, phoenix-like, dies and resurrects, but remains hopelessly enthralled by his beloved. Although his “Father Michael” aspect does not appear again onscreen after Caleb’s first death, that human-like vulnerability, love, and addiction continue to undermine his attempts to seize power. The doppelganger, invisible, unacknowledged, still exerts its self-limiting, self-destructive force.

Caleb in all his self-divided intensity represents the turmoil within us all, the energizing, primordial desires and impulses fighting against conflicting emotions and needs. Manipulative, dangerous, even at times “monstrous,” he is nevertheless a character driven by an all-consuming devotion transcending time and betrayal, a man risking everything to be with his eternal beloved.